Eye For Film >> Movies >> everything (2004) Film Review

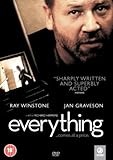

everything

Reviewed by: Anton Bitel

In 2004, two ultra-low budget British films were made that bore a striking, if ultimately superficial, resemblance to one another. Both were shot entirely on Digital Video with a tiny cast and crew, both were divided into nine distinct episodes and both traced the relationship from beginning to end between a man and a woman.

Yet where Michael Winterbottom's 9 Songs articulated the ups-and-downs of its principal characters purely in sexual terms (of an explicit nature unprecedented in a British film on general release), in Richard Hawkins' "everything" no sex ever takes place between Naomi (Jan Graveson) and Richard (Ray Winstone), even if the former is a prostitute and the latter repeatedly visits (and pays) her in the squalid Soho apartment from which she plies her trade.

With hard-nosed, no-nonsense Naomi, "everything's allowed, pretty much", yet she has never had a client like Richard before - mumbling, polite, edgy, and apparently uninterested in any kind of intercourse. During their regular meetings over a nine-day period (the same time it took to shoot the film), he seems content just to interrogate her about her work, her clients and herself, hinting only vaguely that he "might need something else" later. With Naomi struggling both to evade his more personal questions and to determine precisely what he wants, a prickly rapport develops between them, fuelled by tea, cigarettes and various parlour games, until, at last, Richard puts his cards on the table and Naomi finds that her experience is more than adequate to perform the specialised service he requires.

If the opening of "everything" reduces Naomi and Richard to stereotypes, familiar from any red light district (he a heavy-breathing john, struggling unsteadily up a dingy staircase, she introduced on the card outside her door as "young super sexy friendly girl - lips hot"), then the rest of the film gradually strips away our assumptions about them, using the same assured expertise with which Naomi strips off her clothes, until both are revealed in all their naked vulnerability.

Unfortunately in Naomi's case, one stereotype is quickly replaced by another, as she slips all too readily into tart-with-a-heart cliche, which can be forgiven, thanks to the raw desperation and fragile dignity that Graveson, in her cinematic debut, brings to the part. Winstone, on the other hand, portrays a genial, sweaty Richard, who seems more blank than frank, so that we are not sure whether to empathise with his laddish gentleness, or worry about his hulking menace. Sure he is paying her, and sure he wants to exploit her person in a manner that is profoundly humiliating, but this is no ordinary client-prostitute relationship and it is not until near the end of the film that the question about Richard's real motives receives a dramatically satisfying, if not entirely unexpected, answer.

Yet the greater mystery with which "everything" is concerned involves questions about prostitution, for which no such "easy" answers are available: how can men treat women like this and how can women let them?

What Pride & Prejudice does for marriage, "everything" does for the sex industry, offering a kaleidoscopic, if entirely unglamorised, glimpse through the peephole at prostitution in its many, shifting varieties, from a very young Eastern European sex slave to an aging whore to an escort girl working the hotels - all revealed to be women with lives, attachments and identities that go beyond the narrow confines of their trade, but are inevitably (and adversely) affected by that trade.

It is a gritty film, shot with poor lighting that only adds to the general atmosphere of seediness, and any pleasant taste left in your mouth by the vaguely sentimental ending will soon turn sour (or at least tart) if you think about it for long enough. Which is to say that, even if other films from these isles are either cheap imitations of Hollywood, or godawful romantic comedies, at least good old British miserabilism can still turn a new trick or two out on the streets.

Reviewed on: 06 Oct 2005